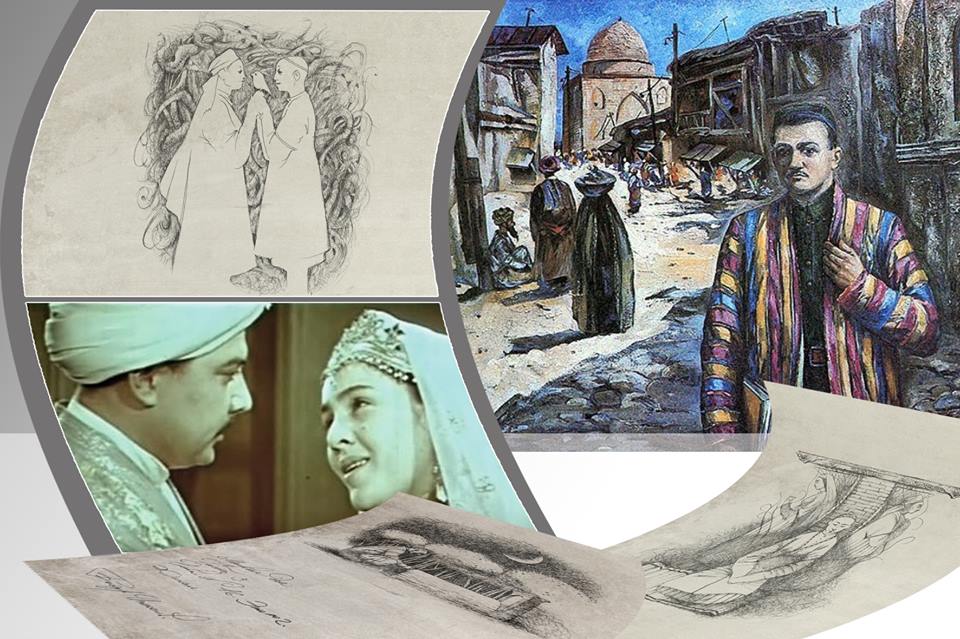

The Islam Karimov Foundation is currently working on the project to translate and publish Abdullah Qadiri’s novel “Days Gone By”

As we reported earlier, the Islam Karimov Foundation is currently working on the project to translate a true masterpiece of the 20th century Uzbek literature into English and French «Days Gone By» by Uzbek author Abdulla Qadiri.

As we reported earlier, the Islam Karimov Foundation is currently working on the project to translate a true masterpiece of the 20th century Uzbek literature into English and French «Days Gone By» by Uzbek author Abdulla Qadiri.

With this novel, Qadiri laid the foundation for the Uzbek school of Romance literature, it is still considered one of Uzbekistan’s most widely read classics. The English translation of the novel is expected to be published this year.

Here we publish excerpts from it.

1. ATABEK, SON OF YUSUFBEK-HADJI

It was the seventeenth day of the month of dalv, hijri (Hijri – Prophet Muhammad’s flight from Mecca to Madina (16 July 622 AD). This event marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar. The date referred to here corresponds to 7 February, 1848.) year 264. A wintry day. Calls to evening prayer rang from all around as the sun set …

Margilan’s famous caravanserai, the one with south-east-facing gates, was packed with merchants from Tashkent, Samarkand and Bukhara. With one or two exceptions, the rooms were overflowing with travellers from afar. Their day’s business done, the lodgers now made their way back to the shelter of the caravanserai, where many of the residents were already bustling about, preparing for the evening meal. Empty by day, this place was now teeming with life: the rising racket of lively conversations interspersed with lusty laughter soared to an indescribable cacophony; the whole compound seemed poised to shoot up into the heavens at any moment.

In the far reaches of the courtyard we see a snug room, marked by the elegance of its décor. If simple koshma felt rugs cover the floors in other rooms, here we find rich crimson carpets; if coarse blankets festoon the other quarters, here they are replaced by kurpach (Kurpach – a traditional quilted mattress stuffed with felt or soft cotton generally covered in silk or cotton, used not only on beds but also in seating areas. (Translator’s note.) ) covers made of silks and adrases (Adras – striped or monotone semi-silk fabrics with colourful designs. (Translator’s note.)) ; if oil lamps smoke in other rooms, here candle flames flicker in a lively dance. And the resident of this room behaves differently, too, not like the hot-headed, happy-go-lucky lodgers in other quarters.

Calm and reserved, of stately build, with a handsome, alabaster face, ebony eyes under equally ebony brows, and a light fuzz of moustache just showing through – such was our young man. In short, both room and resident distinguished themselves from the caravanserai’s other quarters and lodgers. The young man, presently engrossed in thoughts privy to none but himself, went by the name of Atabek. He was the son of an eminent nobleman from Tashkent, Yusufbek-hadji.

Two men entered the courtyard.

“Is this where Atabek is staying?” they enquired of the milling mass.

The room we are already familiar with was pointed out to them, and the visitors set out for it. One of them – a young man, about twenty-five years old, shortish, round-faced, with a sparse beard and moustache – was the son of Ziya-shakhichi, a very well-to-do man from Margilan. He went by the name Rakhmat. The second was about thirty-five years old, lanky, his dark face disfigured by pockmarks. With his flinty eyes and dishevelled beard, he made a most unpleasant impression. Although affluent enough, this man was renowned not for his wealth but for his nickname ‘Hamid-the-Womaniser.’ So popular was this epithet that it had, in fact, become an intrinsic part of his name; should someone refer to him merely as Hamid, others failed to realise who was being referred to. Hamid-the-Womaniser was not acquainted with Atabek, but he was a close relative of Rakhmat, being the latter’s uncle, and Ziya-shakhichi’s brother-in-law.

They both entered the lodgings. Atabek greeted them respectfully, as is proper.

“Forgive us, bek-aka,” (Bek – ruler and leader; in this case, it is used as a polite and respectful form of address, akin to ‘lord.’ Aka – lit. ‘uncle,’ commonly used as a term of respect when addressing one’s elders. (Translator’s note.)) Rakhmat began, “For disturbing you with a visit at this untimely hour.”

Ushering the guests to be seated in the place of honour, Atabek replied with disarming kindness:

“Why no, not at all! You are not disturbing me, far from it! You have greatly gladdened me, since I am visiting your city for the first time and, knowing no-one here, I am quite weary of this enforced seclusion and tedium.”

Meanwhile, a third man entered the room. He, too, bade them welcome. Khasanali, as the old man was called, was around sixty years old, with an oblong face, prominent forehead, round, almost yellow eyes, and a long, snow-white beard. Beard aside, his posture and complexion belied his age.

Atabek seated his guests at the sandal (Sandal – a small, low table over an iron box with hot coals recessed in the floor which serves to warm the feet and legs in winter. (Translator’s note.)) and, after a short prayer, turned to Khasanali:

“How are you feeling, Father?”

“Allah be praised,” replied Khasanali, “It has eased somewhat. I must have inhaled fumes from the coals.”

“Would you do something for me…?”

“State your wish, my son.”

“I would be most grateful if you would boil us some tea.”

“It shall be done, my bek.”

Khasanali left. After enquiring after Atabek’s health once more, Rakhmat asked:

“Bek-aka, how is this person connected to you?”

Atabek fell silent for a while, then glanced at the door. Only when he was satisfied the old man was out of earshot did he reply.

“He is our slave.”

Something about these words startled Hamid.

“Your slave?”

“Precisely.”

When Khasanali was but a boy, Atabek’s grandfather had bought him for fifteen gold tilla (Tilla – a gold coin (Translator’s note.)) from a Turkmen who traded children, kidnapping them in Iran to sell elsewhere. The slave Khasanali had lived with Atabek’s family for almost fifty years now, during which time he had become a true family member. He was eternally devoted to his owner, Yusufbek-hadji, and even more so to his son, Atabek, who treated him with trust and respect. When Khasanali turned thirty, they married him to a bought slave-woman, although the marriage had remained childless, since any babies born died soon after. And so the old man directed all his love and attachment towards Atabek, whom he cherished as his own. “Should he read the prayer from the Koran after my death and remember me with kind words – there once lived a man named Khasanali-ata (Ata – a term of respect, literally ‘father.’ (Translator’s note.)) – then this is more than enough for me,” he thought to himself. Indeed, he had already raised this matter with Atabek and received the latter’s honest assurance that prayers would be said for him. Such was our slave, this simple-hearted old man.

“What have you brought to Tashkent, bek-aka?” Rakhmat enquired once the exchange about Khasanali had subsided.

“Oh, just trifles: fabric, leather for shoes and a few cauldrons.”

“Indeed, fabrics and leather are in great demand at the Margilan cloth markets,” agreed Hamid.

Taking the tongs, Atabek trimmed the candlewick. A certain awkwardness settled over the dastarkhan (Dastarkhan – a Persian word meaning ‘tablecloth’ or ‘great spread,’ widely used in Central Asia to refer to the meal setting as a whole. (Translator’s note.)). The conversation faltered, any comment generally followed by a lengthy silence. In an attempt to alleviate the uncomfortable situation, Rakhmat tried to bolster the flagging chit-chat.

“How do you find our Margilan, bek-aka?” he asked. “Is it to your liking?”

Atabek stalled slightly as he answered, evidently disconcerted.

“How should I put it…? I have taken to it – after all, is not Margilan the foremost city for weaving in the whole of our Turkestan?”

This rather evasive reply caused Hamid and Rakhmat to exchange glances. Catching them, Atabek explained, jokingly:

“Your Margilan has weighed heavy on me since the very day I arrived. Not being acquainted with anyone here, I felt myself an outsider, a stranger. From this moment, however, I can see a different side of Margilan, for now I have found dear friends who took it upon themselves to pay me a visit!”

“Forgive me, bek-aka,” said Rakhmat, “It was only today that I learnt of your arrival in Margilan, from my father. Otherwise, of course, I would not have allowed you to lapse into melancholy.”

“Is that so?”

“My words are true,” said Rakhmat. “My father is hurrying from Tashkent to greet you, yet here you are lodging in the caravanserai! Surely it would be more fitting for us to reproach you?”

“You are right, you are right,” agreed Atabek. “However, firstly, it struck me as wearisome to search out your house, enquiring here and there, and besides, the caravanners are bound to this caravanserai.”

“That may well be, but it is a feeble excuse.”

Khasanali laid the dastarkhan and fetched the kumgan (Kumgan – a copper pitcher with a spout used for washing hands before a meal. (Translator’s note.)), and the guests were served in the traditional manner.

“How old are you, bek?” Hamid asked Atabek, dipping a piece of flatbread into the molasses.

Atabek’s lips had barely begun to move when Khasanali, who was pouring tea, answered for him:

“If Allah grants him days, then in this year of the Monkey, bek will greet the twenty-fourth year of his life.”

“What, am I already twenty-four, father?” bek was surprised. “In all truth, I myself did not know my own age.”

“’T’is true, bek, you are twenty-four.”

Hamid pursued his enquiry.

“Are you married?”

“No.”

Not satisfied by Atabek’s brief ‘no,’ Khasanali deemed it pertinent to explain.

“Although attempts were made more than once to find a suitable bride for our bek,” he said, “Evidently we were not fated to find such a one, and then my bek himself began to resist marriage. Consequently, to this day, we have not been able to arrange a wedding. But our venerable hadji is firmly resolved to marry our bek immediately upon his return from this trip.”

“In my opinion, marriage is the most delicate matter in this world,” said Rakhmat. Turning to Atabek, he went on: “Once married, it is of utmost importance that the wife should suit the husband’s nature. Otherwise, there is no more troublesome task in the whole wide world.”

This statement met with Atabek’s agreement.

“Indeed, without a shadow of a doubt, your words are true,” said he. “I must add, however, that just as the wife should suit the husband, so the husband should fully suit his spouse.”

“If you ask me, whether the husband matches or not is of little import.” Disagreement jarred in Hamid’s voice. “One word is sufficient for any wife: ‘husband’… Nevertheless, as my nephew rightly pointed out, the main thing is that she is suited to her husband.”

Smiling, Rakhmat looked at Atabek, who in his turn was eyeing Hamid with an ironic smile.

“Our marriage is in the hands of our parents,” Rakhmat began, “What of it if the bride is not to the son’s liking? The deciding factor is whether or not she is to the parents’ liking. It is not within the rights of the future bride and groom to declare their preferences, although such customs cannot be applauded as reasonable among what is permitted by sharia. I, for example, married a girl who pleased my parents … Nevertheless, although she was a befitting daughter-in-law for them, she was incompatible with my temperament, and, as you mentioned, most likely she, too, felt a sense of estrangement towards me… Your remark is most astute, bek-aka.”

After listening to Rakhmat with sympathy and attention, Atabek looked at Hamid; what would he say to this?

“Do you hear, nephew?” Hamid turned to Rakhmat. “Of course, you married according to the wishes of your parents, and there is no place for resentment. If your wife is not to your liking, then simply take another, more suited to you, and then you shall have two. And if the second does not please you, marry a third. It is not manly to mope and wallow in misery because of some mismatched temperaments.”

Rakhmat flashed a grin at Atabek, then replied to his uncle:

“What is the sense in increasing the number of wives and the subsequent suffering with them?” said he. “For me, living out one’s life bound to a single, beloved wife is the most reasonable and befitting act. You, for instance, have two wives, and there is not a moment’s peace in your home, merely incessant squabbles and bickering.”

“Indeed, even one wife would overstretch a lad like you!” Hamid chuckled. “And anyway, what does it mean, ‘suffer amid many wives?’ If blood flows from your whip, let there be hundreds – your life will be free of sorrow. Since the day I took my second wife, I have been beset by quarrels, yet I cannot say I am not contemplating taking a third.”

“You are indeed unrivalled in this matter, Uncle.”

Puffing with pride, Hamid glanced at Atabek, who merely smirked in response.

Khasanali went out to prepare pilaf (Pilaf – a traditional Central Asian dish made with meat, carrots, onions, and rice. No social occasion is complete without it. (Translator’s note.)). Atabek served tea to his guests. Hamid’s last words had put an end to their discussion; now, all three seemed engrossed in their own musings. After some time, Rakhmat addressed his uncle:

“Are you aware of whether Mirzakarim-aka given his daughter in marriage yet?” he asked.

For some reason, this question sent a spasm through Hamid and he replied reluctantly:

“I am not aware. But I suppose: not yet.”

Seeking to draw Atabek into the conversation, Rakhmat turned to him.

“Here in Margilan there is one girl… Ah, such a beauty!” he explained. “Were you to search high and low, I do not believe her equal could be found anywhere in these parts.”

Hamid glared sullenly at his nephew, but the young man paid him no heed.

“There is a merchant in our town by the name of Mirzakarim-bai (Bai – an honorific term used for the wealthy. (Translator’s note.)),” he continued, “And this beauty is his daughter. I suppose you are acquainted with Mirzakarim-aka, since he oversaw the Khanate’s financial dealings in Tashkent for some time.”

“No… I do not know him.”

Hamid’s cheerless face grew still more morose; he was obviously nettled.

“His house and courtyard stand on the corner of the shoemakers’ row,” Rakhmat went on, oblivious. “A very well-to-do man. He is acquainted with many respectable folk from Tashkent. Why, your own father is most probably among them.”

“That may well be,” replied Atabek, an involuntary twitch revealing his agitation. Rakhmat noticed nothing, but Hamid caught this momentary flash of emotion. We, however, cannot know whether it was prompted by the conversation, or mere coincidence. The men once again fell silent.

“Bek-aka, when will you pay us the honour of a visit?”

Rakhmat’s question roused Atabek from his reverie.

“When Allah sees fit…”

“No, bek-aka,” Rakhmat was insistent. “You must name the day, for that is why we rode out to you now.”

“Why should I put you to the trouble?”

“There is nothing troubling about it. If you allow us, we shall bring you from the caravanserai to our home. But for now, name the day and grant us the honour of a visit… My father very much wishes to speak with you and learn about matters in Tashkent from your own lips.”

“I would prefer not to leave this caravanserai,” replied Atabek, “But it would be my pleasure to visit your father at any time.”

“Thank you, bek-aka. Won’t you name the day of your visit?”

“As you know, I am at liberty in the evenings, although, should another hour be more convenient for you, I would have no option but to agree.”

“May you enjoy good health!” exclaimed Rakhmat. “Permit me to put another question to you: might we invite strangers when you visit? It would not discomfit you? Allow me to refer once again to the closeness of our social circles, which include, for instance, Mirzakarim Kutidor (Kutidor –a money changer. Used as a post-nominal title to indicate an eminent or wealthy merchant. Often used to substitute the name itself, as is the case in this novel. (Translator’s note.)).”

Flustered once again, but seeking to conceal it, Atabek replied simply:

“As pleases you.”

After pilaf, the guests said their farewells and left.